HANUKKAH TOWN

ABOUT THE HOLIDAY

THE HISTORY OF HANUKKAH

This is how that story goes: We begin well before the miraculous event, when Antiochus III, a Seleucid (Greek) conquered Judea in 200 BCE. Eventually the region was ruled by Antiochus IV who looted the Second Temple, the center of the Jewish world.

In 167 BCE, Antiochus ordered an altar built to Zeus, the Hellenistic god. The Seleucids were destructive of the Temple in other ways as well–sacrificing unkosher animals like pigs on the altar, destroying the oil supplies meant for the eternal flame, and forbidding important ritual practices of the Jewish people.

Mattathias, a Jewish priest, and his five sons, led a rebellion. At the core of the conflict were Jews who supported the Hellenists. The first to be killed by Mattathias was one loyal to the Greeks, but quickly, Mattathias’ son, Judah Maccabee (Judah the Hammer), had become the hero of the war.

After his father died, he took over as leader of the revolt, concluding a lengthy series of battles, by rededicating the Second Temple on Kislev 25 in the year 165 BCE.

When that happened, there was only one remaining day’s worth of oil blessed by the High Priest.

The miracle that took place was that the oil, only enough for one day, lasted for eight while the High Priest made and consecrated more.

Later, this eight-day festival was established to celebrate the victory and the associated miracle.

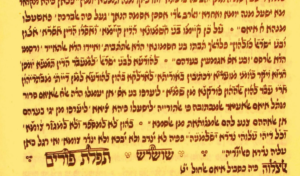

There are lots of ways to interpret the name, “Hanukkah,” but the simplest is that it comes from the root “Chanach” which means, “dedicate.” There are a range of historical sources for what we know of the holiday, from the apocryphal books, 1st and 2nd Maccabees. These are not texts that are part of the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible, but are included in Catholic and Orthodox versions of the Old Testament, so the text is readily available. It makes reference to the rededication of the Second Temple and to a previous fire-lighting miracle with Nehemiah on the same date in the Jewish calendar, Kislev 25. 2nd Maccabees also provides an analogy to the eight-day celebration of Sukkot, in how the holiday should be commemorated. In terms of accepted Jewish sources, we have rabbinic commentary in the 1st century CE referring to the eight days of Hanukkah to be observed, but no details as to why or how.

Even in the late 2nd century, there are few details and few mentions of the holiday. Some have speculated that the rabbis writing the Mishnah didn’t want to make a big fuss about the celebration of a past revolt, while they were under Roman rule, which might make the Romans nervous.

It’s also possible that the practice was so common, that they didn’t feel the need to explain it. It isn’t until some later passages of Talmud that we get the full story of the miracle of the oil and lots of discussion about candle-lighting practices.

Some argue that we should light a single candle each night; some that we should light eight on the first, seven on the second, and so on; others argued for the practice that is most common today, that we light one on the first and increase the number each night. There is even debate about whether the candles should be put into the hanukkiah each night from right to left or left to right and whether we light those candles left to right or right to left. Typically of Jewish practice, there are many variations on how anything should be done.

The Maccabees, and particularly Judah Maccabee, have become revered figures in Judaism and in the nation of Israel, in matters of war and sport.